Across the 11 countries surveyed, people’s attitudes toward mobile phones tend to be largely positive. In most of the countries, a large majority say mobile phones have been good for them personally, and many also say mobile phones positively impact education and the economy. Mobile phone users also overwhelmingly agree that their phones help them to stay in touch with faraway friends and family and keep them informed of the latest news and information.

At the same time, people’s positive attitudes are paired with concerns about the impact of mobile phones on certain aspects of society – and especially their impact on children. In eight of these countries, a majority of the public says that the increasing use of mobile phones has had a bad impact on children today. And when asked about the potential risks of mobile phone use, majorities in every country say people should be very concerned that mobile phones might expose children to harmful or inappropriate content.

I think mobile phones have made the world like a global village. MAN, 24, KENYA

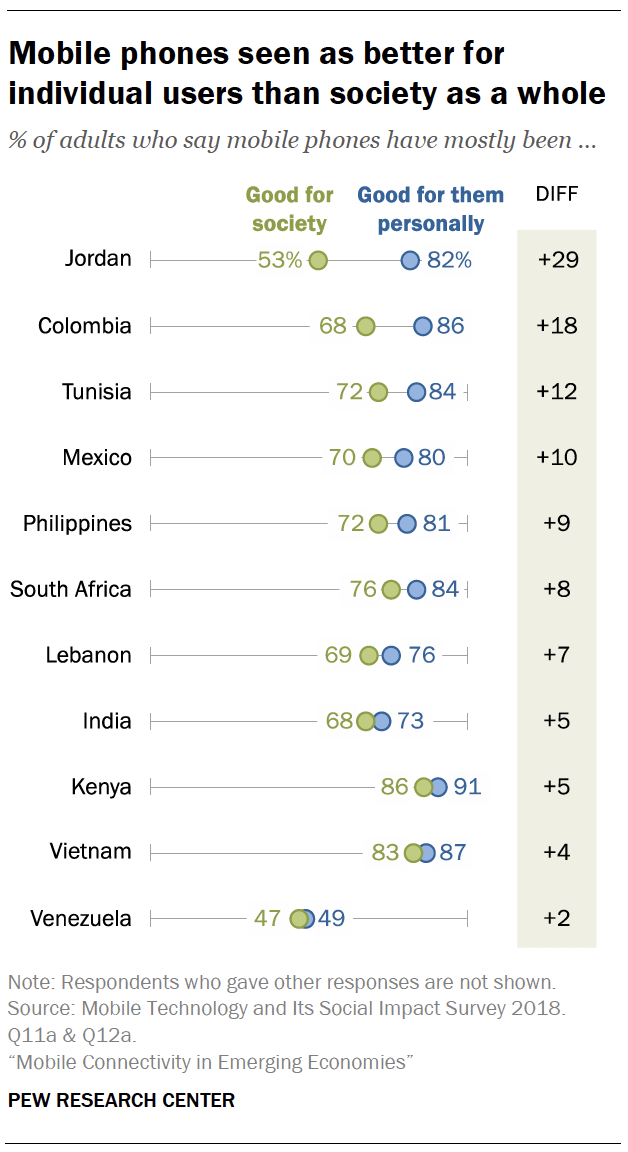

In nine of the 11 countries surveyed, large majorities say mobile phones have been mostly good for them personally. In Venezuela, people are more skeptical of the role mobile phones are playing in their lives. There, 49% say mobile phones have been mostly good for them personally, while 47% say they have been mostly bad. Elsewhere, no more than 11% in any country say mobile phones have been mostly a bad thing for them.

In nine of these 11 countries, majorities also say mobile phones have had a positive impact on society. But in most countries, people report less enthusiasm about the societal impact of mobile devices than about their personal impact. For example, while 82% of Jordanians say mobile phones have mostly been good for them personally, just 53% express positive views about their societal impact. And in Colombia, Tunisia and Mexico, there is at least a 10-percentage-point difference between shares who see the personal benefits of mobile phones and those who see the society-wide benefits.

Regardless of the type of mobile phone people use – basic, feature or smart – most have similar views about how their lives and societies have been impacted by their devices. 9 Across all surveyed countries, basic or feature phone users are just as likely as smartphone users in their country to say mobile phones have mostly been a positive thing for them personally. And in all countries but Mexico, similar shares of smartphone users and those with less advanced devices say the societal impact of mobile phones has mostly been good. In Mexico, where smartphone use is relatively low compared with other countries, smartphone users are somewhat more likely than basic or feature phone users to say the impact on society has been mostly positive (77% vs. 69%).

But there are some differences between mobile phone users and those who do not use a mobile phone at all. In five of these 11 countries (India, Kenya, Lebanon, Mexico and South Africa), mobile users of any kind are more likely than non-users to say that mobile devices have had a mostly positive impact on society.

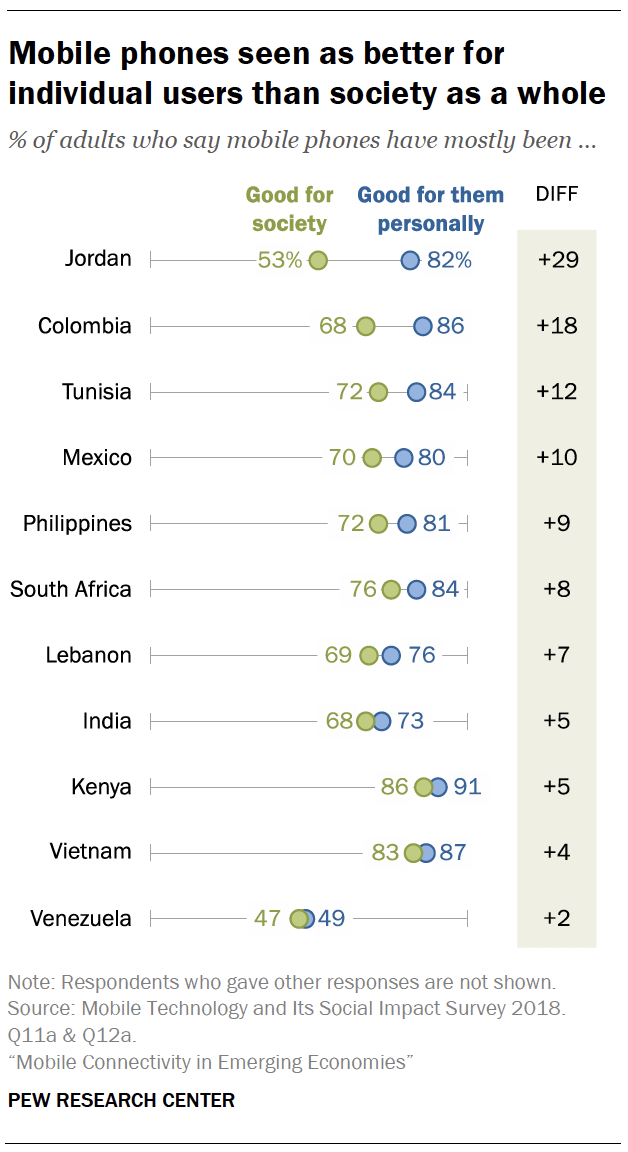

In every country surveyed, mobile phone users are more likely to say their phone is something that frees them rather than something that ties them down. At least 63% in five countries (Kenya, Vietnam, Venezuela, South Africa and the Philippines) characterize their phone as something that frees them, whereas users in other countries are somewhat more ambivalent. For example, while 46% of Jordanian mobile phone users say their phone frees them, 25% say it ties them down, and 21% volunteer that neither statement holds true. In Lebanon, 40% of mobile phone users say their phone frees them, compared with 30% who say it ties them down.

“It’s like the mobile phones become your partner. WOMAN, 40, PHILIPPINES

Across the 11 countries surveyed, mobile phone users are somewhat more divided when it comes to whether their phone helps save them time or makes them waste time. In seven countries, larger shares say their phone helps save them time. Kenyans are especially likely to see their phone as a time saver; 84% of mobile phone users say their phone saves them time, compared with 14% who say it wastes their time. Venezuelan (71%), South African (65%), Indian (64%), Vietnamese (63%), Tunisian (54%) and Colombian (50%) phone users are also more likely to say that phones save them time rather than waste it. But mobile phone users in Jordan and the Philippines generally believe they waste more time on their phones than they save, while Mexican and Lebanese phone users are roughly evenly divided in their assessments.

Mobile phone users are even more divided when assessing their reliance or lack thereof on their mobile device. In six countries – Mexico, Colombia, India, the Philippines, Venezuela and Vietnam – around half or more see their phone as something they don’t always need. But in five others – Jordan, Lebanon, South Africa, Tunisia and Kenya – users are more inclined to say they couldn’t live without it.

In some instances, people’s perceptions of the necessity of their mobile device is not linked to their assessments of its utility in other aspects of their life. For instance, a majority of Venezuelans say their phone is something that frees them and helps them save time – but just 29% say they couldn’t live without it. Conversely, a majority of Jordanians say they couldn’t live without their phone – even as they are more likely to describe it as a time waster rather than a time saver.

Consistently, smartphone users tend to be somewhat more critical of their device than basic or feature phone users in their country. For example, in every country smartphone users are more likely than basic or feature phone users to say their phone makes them waste time. And in all countries except Lebanon, smartphone users are more likely to say their phone ties them down rather than frees them.

There are also prominent and consistent differences by age. In every country surveyed, mobile phone users ages 50 and older are significantly more likely than users ages 18 to 29 to believe their phone helps them save time. The age gap is particularly notable in Vietnam, Tunisia and Colombia, where the shares of older adults who see their phone as a time saver surpass those of younger adults by at least 27 percentage points. And, while it is true that younger adults use smartphones and social media at higher rates than older adults, in every country but India these age differences persist even when accounting for age-related differences in usage.

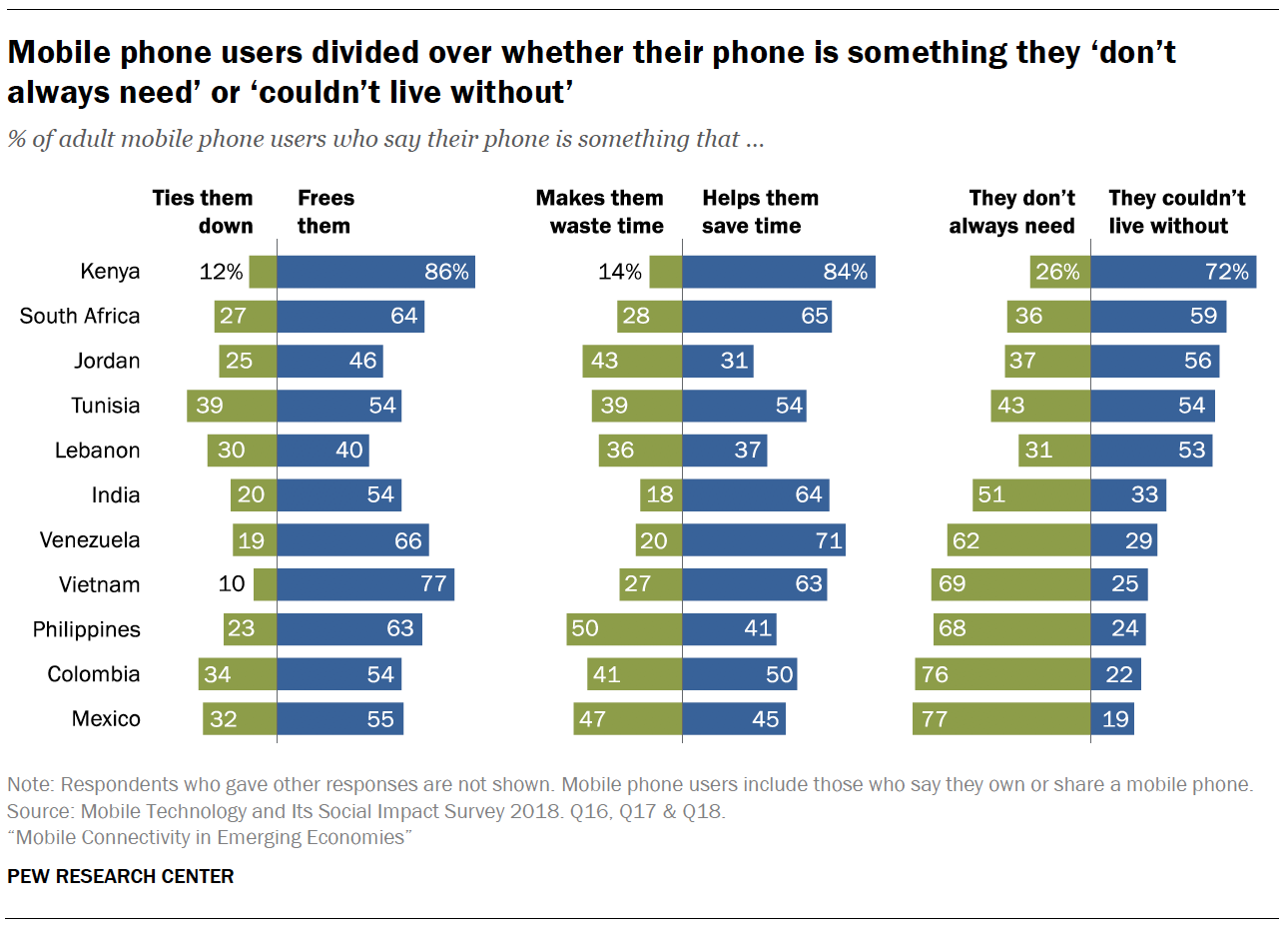

When asked about a variety of ways in which mobile phones might affect their day-to-day lives, users across the surveyed countries generally agree that mobile phones have mostly helped them keep in touch with people who live far away and obtain information about important issues. But there is less consensus when it comes to mobile phones’ impact on people’s ability to earn a living, concentrate and get things done, or communicate face-to-face.

In general terms, communication is much more efficient. You are more interconnected, [whether] with your relatives or with world affairs. MAN, 26, MEXICO

Large majorities say their phones have mostly helped them stay in touch with people who live far away. A median of 93% across the 11 countries surveyed express this view, whereas a median of just 1% say mobile phones have hurt their ability to stay in touch. Majorities also say their mobile phones have helped them obtain information and news about important issues, ranging from a low of 73% in Vietnam to a high of 88% in Kenya. And only small shares (from 1% to 6% of users) indicate that phones have hurt their ability to do this.

In all 11 countries, smartphone users are significantly more likely than basic or feature phone users to say their phone has helped them obtain news and information. The difference is particularly prominent in Lebanon, where 83% of smartphone users say the impact has been positive, compared with 26% of non-smartphone users. And in Jordan, smartphone users are much more likely than non-smartphone users to say their phone has mostly helped them obtain information (83% vs. 44%).

Across the 11 countries surveyed, there is less agreement about whether mobile phones have helped people earn a living. Majorities of users in nine countries say their phone has had a positive impact on their livelihood – ranging from 55% in Tunisia to 81% in Kenya – while Jordanians and Lebanese most commonly say that mobile phones have not had much impact either way on their ability to make a living. Still, few people see mobile phones having a negative effect. Even in Jordan and Lebanon, nearly four-in-ten say the impact has been favorable.

There is less consensus among mobile phone users that their devices have helped them to concentrate and get things done. Majorities in eight out of 11 countries say mobile phones have mostly helped them concentrate and get things done. But notable shares in the Philippines (30%), Lebanon (18%) and India (16%) say mobile phones negatively affect their concentration.

In some instances, these attitudes are related to the type of device users carry – although this relationship varies by country. Smartphone users in five out of 11 countries – Lebanon, India, Jordan, Colombia and Venezuela – are more likely than other phone users to say their phone helps them concentrate and get things done, while there are no differences based on smartphone usage in the other six countries surveyed. This pattern is particularly salient in Lebanon, Jordan and India, where smartphone users and non-smartphone users differ by at least 10 percentage points.

These findings echo the concerns raised by some focus group participants (see Appendix A for more information on how the groups were conducted). Some respondents noted how mobile phones bring distractions and shorten their attention spans, leading people to commit basic errors or not complete work because of the attention paid to their devices. In every group held in the Philippines, for example, at least one participant brought up that she had burned the rice she was making because of her focus on her phone.

Because I was busy texting my client, my rice got overcooked. WOMAN, 40, PHILIPPINES

Lastly, majorities of users in eight countries say their mobile phones have helped their ability to communicate face-to-face – but notable shares in many countries say that impact has been mostly negative. In particular, 35% of Lebanese phone users say mobile phones have hurt their ability to communicate face-to-face.

In focus groups, some lamented that more and more people prefer virtual communication enabled by mobile phones and other technologies to face-to-face interaction. A few participants across the four countries where focus groups were conducted also pointed out similar trends among children and young people.

People meet less because of their phones; people use telephones to express themselves to avoid face-to-face discussions. MAN, 23, TUNISIA

Because these questions center on people’s personal relationship with their device, they were only asked of those who own or regularly share a mobile phone. For those who reported not using a phone at all, a different set of questions were posed: How do mobile phones, in general, shape people’s ability to stay in touch with those far away, to obtain information, and so on? Broadly, non-users’ impressions of the impact of mobile phones tend to mirror the ways users feel about their own devices. The vast majority of non-users feel that mobile phones help people stay in touch with those who live far away, but smaller shares think they help people to concentrate and get things done or communicate face-to-face.

Publics in the 11 nations polled view mobile phones as having a range of positive and negative consequences when it comes to their broader impact on their country and its society. Most notably, a median of 67% – and around half or more in every country – say the increased use of mobile phones has had a good influence on education. Slightly smaller majorities say the increased use of mobile phones has had a good influence on the economy (58%) as well as on their local culture (56%).

My kid’s always on his phone, and every time I address him he just nods while on his phone. WOMAN, 46, MEXICO

Across all dimensions measured in the survey, publics in the 11 countries are most negative about the impact of mobile phones on children. Nowhere does a majority feel that mobile phones have had a good influence on children. And in eight countries, majorities of the population say that mobile phones have had a bad influence on children today. Residents of the three Middle East and North African (MENA) countries surveyed are especially downbeat about mobile phones in this regard: 90% of Jordanians, 86% of Lebanese and 81% of Tunisians say mobile phones have had a bad influence on children in their country.

In addition to the impact of mobile phones on children, health and morality stand out as particular areas of concern. A median of 40% – and clear majorities in Lebanon (71%), Jordan (69%) and Tunisia (63%) – say the increasing use of mobile phones has had a bad influence on people’s physical health. Some focus group participants expressed similar sentiment by commenting that excessive screen time, phone “addiction” and lack of physical activities were potential health-related challenges.

Meanwhile, a median of 34% say mobile phones have had a positive impact on morality, similar to the share who say the impact has been negative. As was the case with children and health, Lebanese, Jordanians and Tunisians hold the most unfavorable views in this regard. Roughly a third or more in Colombia, Mexico, Kenya and South Africa also say mobile phones negatively affect people’s morality.

Phones also give us much more room to conceal things. MAN, 42, MEXICO

As noted above, publics in Lebanon, Jordan and Tunisia stand out in their overall negativity toward mobile phones on these aspects of society. But other countries are conspicuous for having relatively positive attitudes in this regard. Kenyans, in particular, offer especially upbeat assessments of mobile phones. Half or more Kenyans feel that mobile phones have had a positive impact on each of these aspects of society, with the exception of children today (just 28% of Kenyans say mobile phones have been good for children). South Africans and Filipinos are also relatively positive about most areas surveyed.

In most countries, there are no differences between smartphone users and non-users – nor between social media users and non-users – when it comes to people’s views about the impact of increasing mobile phone use on children. But on other questions there is more variation between users and non-users. For instance, in six out of 11 countries larger shares of social media users than non-users say the increasing use of mobile phones has had a good influence on their nation’s politics. This includes all three MENA countries in the survey. Conversely, in eight of these 11 countries larger shares of social media users than non-users say mobile phones have had a bad influence on family cohesion.

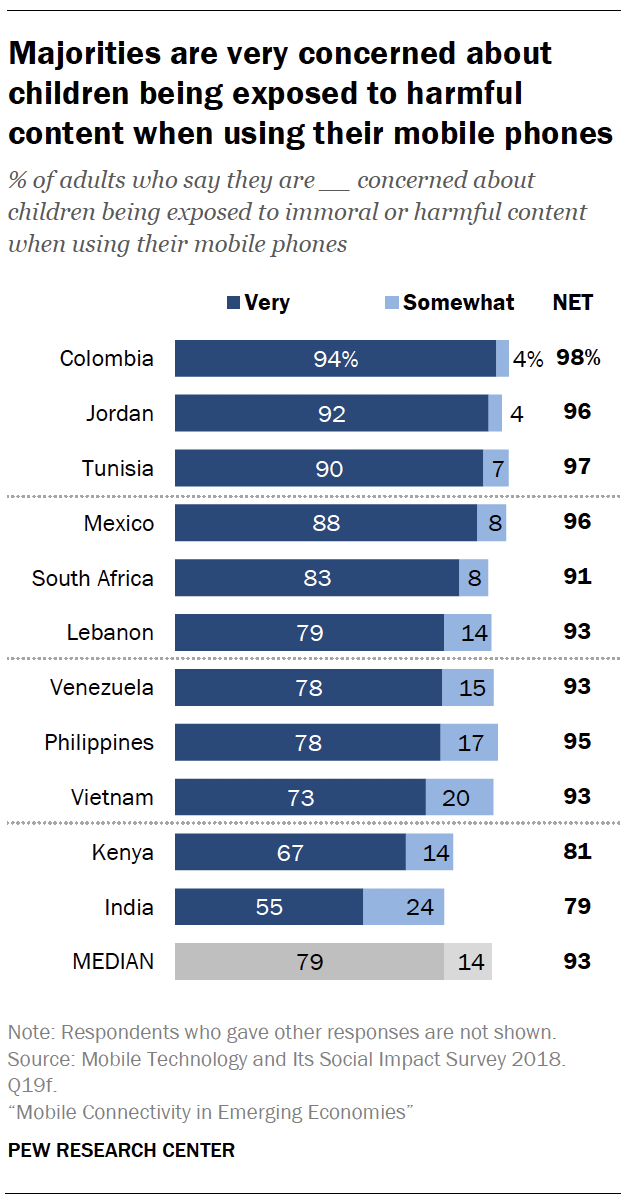

Despite the perceived benefits of increased mobile adoption in areas such as education, publics express concern about an array of potential downsides of mobile phone use. The survey asked about six possible risks from mobile phone use, and respondents in every country are most concerned about children being exposed to immoral or harmful content. A median of 79% – including a majority in each country surveyed – feel people should be very concerned about this.

Meanwhile, the prospect of users losing their ability to communicate face-to-face is the item of least concern in each country. In only two countries (South Africa and Colombia) are a majority of adults very concerned about declining face-to-face communication skills as a result of mobile phone usage.

Among these 11 countries, Colombians rank in the top two most-concerned about all of these issues. Other countries that rank in the top two most-concerned on particular issues include: Mexico (identity theft and online harassment); Jordan (phone addiction and impacts on children); South Africa (exposure to false information and losing the ability to talk face-to-face); and Tunisia (phone addiction).

Beyond these country-specific differences, concerns about mobile phone use exhibit few consistent or substantial differences relating to gender, age, phone type or social media usage. Notably, concerns about children are widespread across multiple groups. In most instances, men and women, older and younger adults, and social media users and non-users express similar levels of concern about the impact of inappropriate online content on children.

Additionally, men and women in most of these countries are similarly concerned about harassment and bullying – a noteworthy contrast to the gender-related differences often seen in surveys of online harassment among Americans. For example, a 2017 Pew Research Center survey found that 70% of women in the U.S. said online harassment was a “major problem,” compared with 54% of men.

“Sometimes I try to use [my phone] less, but it only lasts for two or three days and then I come back to the daily rhythm. WOMAN, 21, TUNISIA

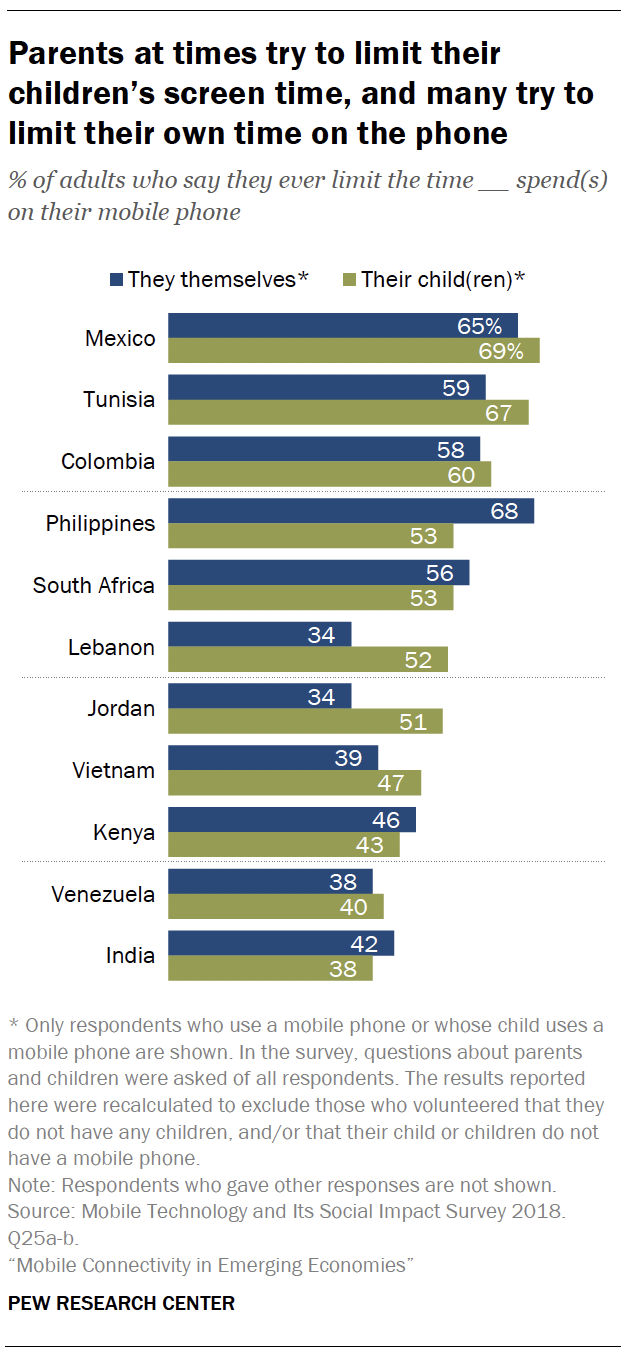

Amid a widespread debate over the impact of various types of screens on children and adults alike, majorities of mobile phone users in five of these 11 countries say they have ever tried to limit the time they themselves spend on their phone. This behavior is especially common in the Philippines and Mexico, but somewhat less prevalent among mobile phone owners in Jordan, Lebanon, Venezuela and Vietnam.

In all 11 countries surveyed, smartphone users are more likely than non-smartphone users to say they try to limit the time they spend on their mobile phone. These differences are especially prominent in Vietnam (where 46% of smartphone users and 24% of non-smartphone users have done this) and Colombia (66% vs. 45%). And in 10 of these countries, larger shares of mobile phone users who also use social media say they have tried to limit their phone use relative to those who do not use social media.

People’s efforts to limit screen time also extend to children. Among parents whose child has access to a mobile phone, about half or more in seven of these countries say they ever set limits on how much time their child can spend on their phone. 10

As was true of limiting their own screen time, parents’ efforts to limit the time their child spends on his or her phone also differ by the type of phone they themselves own. 11 Smartphone-owning parents whose child also uses a mobile phone are more likely than parents with more basic phones to say they have tried to limit their child’s screen time in nine of these 11 countries. Indeed, this gap reaches double digits in nine of these 11 countries – and is as high as 22 points in Vietnam and Jordan.

Parents’ efforts to limit their child’s mobile phone use are also related to their concerns about the negative impacts of mobile phone use (such as online harassment or children being exposed to immoral content). In nearly every country surveyed, parents who say they are very concerned about at least five of the six issues tested are more likely to try to limit their child’s mobile phone use relative to those who are very concerned about two or fewer of these issues. The only exception to this trend is Jordan, where similar shares of highly concerned and less-concerned parents say they try to limit their child’s mobile phone use.

“You should be the one limiting your child. It’s up to you to make ways to be able to limit the problems that you encounter. That’s why even if my child is very interested with gadgets, he is consistently in the honor rolls … I make limitations.” WOMAN, 38, PHILIPPINES

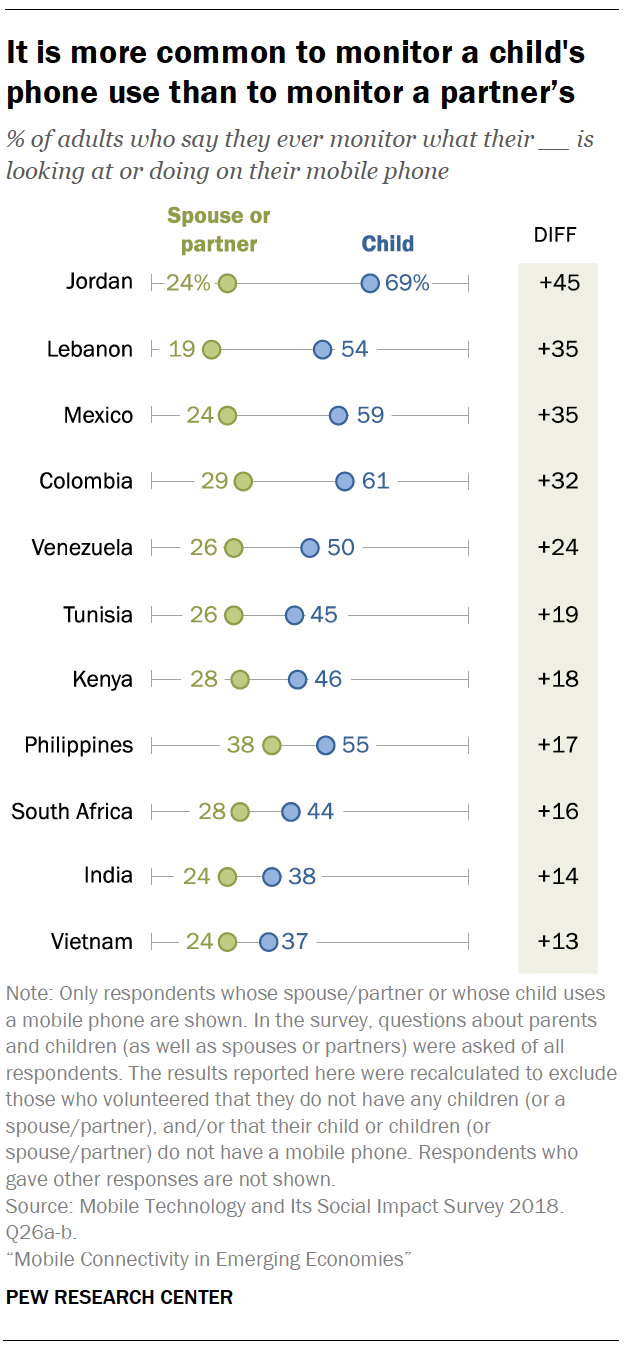

In the focus group interviews conducted as part of this study, mobile phone surveillance performed by immediate family members emerged as a common theme. Some parents mentioned that mobile phones allowed them to track the whereabouts of their children and to make sure they were not exposed to harmful content. And for people in marriages or romantic relationships, mobile phone “spying” and social media “stalking” sometimes become the source of drama, jealousy and harassment.

Among parents whose child or children use a mobile phone, a median of 50% say they ever monitor what their child is looking at or doing on the screen. But some variation exists across these countries. In Jordan, Colombia and Mexico, for example, clear majorities of parents do this, compared with 37% of parents in Vietnam and 38% in India.

Parents who use a smartphone are generally more likely to say they monitor their child’s phone usage than parents who use a basic or feature phone. This trend is seen in 10 out of the 11 countries and is especially prominent in Jordan and Vietnam, where smartphone users differ from other phone users by 30 percentage points each.

Parents’ likelihood of monitoring their child’s phone use also differs by their own social media presence. Parents who use social media and messaging apps in each country are more likely than parents who do not use social media platforms to say they monitor content on their child’s phone.

In all countries surveyed, it is less common to monitor a partner’s phone activity – although notable shares of those with a spouse or partner report doing so. 12 Among those whose partner or spouse uses a mobile phone, a median of 26% say they ever monitor their partner’s phone use. In the Philippines, this behavior is somewhat more common; 38% say they monitor their partner’s phone.

In most countries surveyed, younger adults are more likely to monitor their partner’s phone than older adults in their country. This trend holds even after accounting for the fact that younger adults are generally more likely than older adults to use smartphones or social media. In 10 countries, smartphone users ages 18 to 29 are more likely to say they monitor their partner’s phone activity than smartphone users ages 50 and older.

There are also notable gender differences when it comes to monitoring the phone activity of their significant other. In five of these 11 countries (Jordan, Venezuela, Vietnam, Mexico and Tunisia), larger shares of women than men say they ever monitor what their partner does on the phone. India is the only country surveyed where men are more likely than women to say they keep an eye on their partner’s phone.

When a guy commented on my post, my husband got jealous about it. WOMAN, 27, PHILIPPINES Talking from a married point of view, I think it’s brought a lot of mistrust. If my data is on at 10 in the night and someone sends something on WhatsApp, it’s always suspect. Who’s texting at 10? My husband is often suspicious. WOMAN, 32, KENYA

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings